Hi Folks,

Usability is not easy to define. The meaning of ‘usability’ is sometimes reduced to “easy to use,” but this over-simplifies the problem and provides little guidance for the user interface designer. There are a few basic characteristics of usability which helps guide the user-centered design tasks to the goal of usable products.

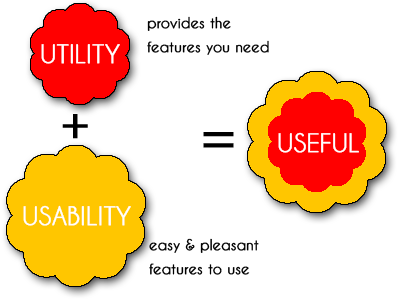

There are many other important quality attributes. Before going deeper into Usability – we would be digging into another attribute – utility, which refers to the design’s functionality.

Usability and utility are equally important and together determine whether something is useful: It matters little that something is easy if it’s not what you want. It’s also no good if the system can hypothetically do what you want, but you can’t make it happen because the user interface is too difficult. To study a design’s utility, you can use the same user research methods that improve usability.

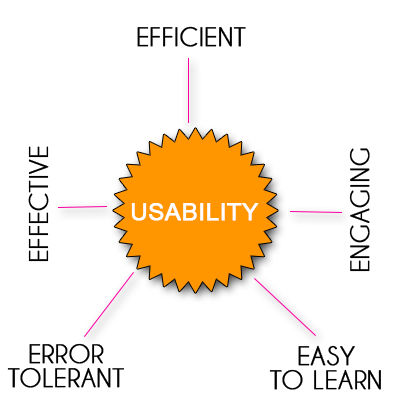

Now coming back to Usability, we can define it by elaborating the 5 Es – efficient, effective, engaging, error tolerant and easy to learn. These 5 Es describe the multifaceted characteristics of usability. Interfaces are evaluated against the combination of these characteristics which best describe the user’s requirements for success and satisfaction.

- Effective

Effectiveness is the completeness and accuracy with which users achieve specified goals. It is determined by looking at whether the user’s goals were met successfully and whether all work is correct.

It can sometimes be difficult to separate effectiveness from efficiency, but they are not the same. Efficiency is concerned primarily with how quickly a task can be completed, while effectiveness considers how well the work is done. Not all tasks require efficiency to be the first principle. For example, in interfaces to financial systems (such as banking machines), effective use of the system — withdrawing the correct amount of money, selecting the right account, making a transfer correctly – are more important than marginal gains in speed. This assumes, of course, that the designer has not created an annoying or over-controlling interface in the name of effectiveness.

- Efficiency

Efficiency can be described as the speed (with accuracy) in which users can complete the tasks for which they use the product. ISO 9241 defines efficiency as the total resources expended in a task. Efficiency metrics include the number of clicks or keystrokes required or the total ‘time on task’It is important to be sure to define the task from the user’s point of view, rather than as a single, granular interaction. For example, a knowledge base which doled out small snippets of information might be very efficient if each retrieval was considered one task, but inefficient when the entire task of learning enough to answer a user’s question is considered.

- Engaging

An interface is engaging if it is pleasant and satisfying to use. The visual design is the most obvious element of this characteristic. The style of the visual presentation, the number, functions and types of graphic images or colors (especially on web sites), and the use of any multimedia elements are all part of a user’s immediate reaction. But more subtle aspects of the interface also affect how engaging it is. The design and readability of the text can change a user’s relationship to the interface as can the way information is chunked for presentation. Equally important is the style of the interaction which might range from a game-like simulation to a simple menu-command system.

- Error Tolerant

The ultimate goal is a system which has no errors. But, product developers are human, and computer systems far from perfect, so errors may occur. An error tolerant program is designed to prevent errors caused by the user’s interaction, and to help the user in recovering from any errors that do occur.

Note that a highly usable interface might treat error messages as part of the interface, including not only a clear description of the problem, but also direct links to choices for a path to correct the problem. Errors might also occur because the designer did not predict the full range of ways that a user might interact with the program. For example, if a required element is missing simply presenting a way to fill in that data can make an error message look more like a wizard. If a choice is not made, it can be presented without any punitive language. (However, it is important to note that it is possible for an interface to become intrusive, or too actively predictive.)

- Easy to Learn

One of the biggest objections to “usability” comes from people who fear that it will be used to create products with a low barrier to entry, but which are not powerful enough for long, sustained use.

But learning goes on for the life of the use of a product. Users may require access to new functionality, expand their scope of work, explore new options or change their own workflow or process. These changes might be instigated by external changes in the environment, or might be the result of exploration within the interface.